by Katharine H. S. Moon

Tell me the difference between comfort women and bar girls/ kijich.

U.S. military-oriented prostitution in Korea is not simply a matter of women walking the streets and picking up U.S. soldiers for a few bucks. It is a system that is sponsored and regulated by two governments, Korean and American (through the U.S. military).The U.S. military and the Korean government have referred to such women as "bar girls," "hostesses," "special entertainers," "businesswomen," and "comfort women." Koreans have also called these women the highly derogatory names, yanggalbo (Western whore) and yanggongju (Western princess)

The vast majority of these women have experienced in common the pain of contempt and stigma from the mainstream Korean society. These women have been and are treated as trash, "the lowest of the low," in a Korean society characterized by classist (family/educational status-oriented) distinctions and discrimination. The fact that they have mingled flesh and blood with foreigners (yangnom) 4 in a society that has been racially and culturally homogeneous for thousands of years makes them pariahs, a disgrace to themselves and their people, Korean by birth but no longer Korean in body and spirit. Neo-Confucian moralism regarding women's chastity and strong racialist conscience among Koreans have branded these women as doubly "impure." The women themselves bear the stigma of their marginalization both physically and psychologically. They tend not to venture out of camptowns and into the larger society and view themselves as "abnormal," while repeatedly referring to the non-camptown world as "normal." Once they experience kijich'on life, they are irreversibly tainted: it is nearly impossible for them to reintegrate themselves into "normal" Korean society. Kim Yang Hyang, in the documentary The Women Outside, recalls how her family members rejected her when she returned to her village after working for a time in the kijich'on. One of her cousins told her, "Don't come around our place."

"Too different" was a polite way of saying what many Korean activists and academics today, even those who advocate on behalf of the former Korean "comfort women" to the Japanese military in World War II, still believe--kijich'on prostitutes work in the bars and clubs because they voluntarily want to lead a life of prostitution, because they are lacking in moral character. This kind of academic and activist negligence of kijich'on prostitutes is a function of the Korean society's bias against these women--that they are an "untouchable" class, that they have already departed so far from the norms and values of mainstream society to deserve consideration of the political, economic, and cultural sources of their unenviable existence.

American Town is like many of the other numerous camptowns near or adjoined to major U.S. military camps in South Korea. Like no other places in Korea, Americans and Koreans together make up the residents of the kijich'on.

What distinguishes American Town from the other camptowns is its physical isolation--it is completely walled off, with a guard posted at the gate--and its"incorporated" status. American Town is not simply a place; it is a corporation, with a president and board of directors who manage all the businesses and people living and working in it. The corporation headquarters occupies a small building within the walled compound. Originally, the Town was constructed in the early-to-mid 1970s through funds from both the local government and Seoul

There are two types of kijich'on prostitutes, the registered and the unregistered, or so-called streetwalkers. This book is about the first group of women, who are the governmentally recognized"special entertainers." Registered women sell drinks, dance with GIs, and pick up their customers in the kijich'on clubs. These women have more job security than streetwalkers because they have official sanction to sell their flesh. Moreover, they have a regular establishment from which they can attract customers, and they will not be hauled off to jail for prostitution, unlike streetwalkers, unless their official identification cards are invalid.

In order to work in the clubs, a woman must go to the local police station to register her name and address and the name of the club where she will be working. She must also go to the local VD clinic, undergo gynecological and blood examinations and receive a VD card.

Moreover, to sell drinks, she must mingle with various GIs in one night, fondling them and being fondled by them in return. On the average, in the mid-1990s, clubs were paying a hostess $250 a month. 9 Selling drinks, however, has never been the mainstay of the women's earnings: Women are expected to sleep with GIs for the bulk of their income because their cut from selling drinks cannot support them, and"[m]any places don't pay any salary." 10 In Uijongbu in the mid-1980s,"long-time" (overnight) was $20, while"short-time" (hourly rate) was $10. 11 Owners and pimps generally take 80% and give the prostitute 20% of her earnings per trick.

Most women do not come into the clubs equipped with"hostessing skills" and the willingness to share flesh with GIs. For women who are new to the club scene, an initiation process often takes place. Some women attest to having been raped by their pimp/manager; others have been ordered by the club owner to sleep with a particular soldier; yet others stumble into bed with GIs on their own; some receive advice on the type of man to avoid (e.g., violent types) from more experienced prostitutes.

Both the prostitutes and U.S. military officials have observed that club women aggressively seek out customers. In Camp Arirang, Kim Yonja recalls how she and other women grabbed onto men in order to make money.

How prostitutes fare physically, financially, and emotionally in the kijich'on environment depends to a great extent on the particular club owner/manager and GI customers she encounters. As"Nanhee" says, some GIs are mean and nasty, especially when they are drunk; others are nice and gentle. 18 At worst, a woman encounters a GI who beats her and murders her, as Yun Kumi did in October 1992. Private Kenneth Markle was convicted of killing her; her landlord found her body--"naked, bloody, and covered with bruises and contusions--with laundry detergent sprinkled over the crime site. In addition, a coke bottle was embedded in Yun's uterus and the trunk of an umbrella driven 27 cm into her rectum."

The"debt bondage system" is the most prominent manifestation of exploitation. A woman's debt increases each time she borrows money from the owner--to get medical treatment, to send money to her family, to cover an emergency, to bribe police officers and VD clinic workers. Most women also begin their work at a new club with large amounts of debt, which usually results from the"agency fee" and advance pay. Typically, (illegal) job placement agencies which specialize in bar and brothel prostitution place women in a club and charge the club owner a fee. The owner transfers the fee onto the new employee's"account" at usurious rates; Ms. Pak mentions one club owner charging 10%. 25 Often, women ask the owner for an advance in order to pay off her existing debts to another club, and the cycle of debt continues. Owners also set up a new employee with furniture, stereo equipment, clothing, and cosmetics--items deemed necessary for attracting GI customers. These costs get added to the woman's account with interest. In 1988, the left-leaning Mal Magazine (Malchi), reported that on the average, prostitutes' club debts range between one and four million won 26 ($1,462 and $5,847 respectively in 1988 terms). For this reason, women try to pick up as many GIs as possible night after night, and for this reason, women cannot leave prostitution at will. Nanhee sums up the debt-ridden plight:

>

The great majority of women who enter kijich'on prostitution have already experienced severe deprivation and abuse--poverty, rape, repeated beatings by lovers or husbands. The camp followers of the war era lived off their bodies and fed their family members with their earnings. Korean camptown officials who had lived through the war expressed sympathy for the early generations of prostitutes when I interviewed them in 1992. Their sentiment was such:"All of us Koreans back then--educated or uneducated--were dirt poor; we were all in the same boat and were forced to do things beneath our dignity to survive."

Poverty, together with low class status, has remained the primary reason for women's entry into camptown prostitution from the 1950s to the mid-1980s.Stories of growing up with no plot of land or high debts from farming attempts, going hungry amidst eight or nine siblings, barely finishing a few years of schooling, and tending to ill parents resound among kijich'on women. Many of these women were part of the migration flow from the countryside to the cities in the 1960s. 28 They left their villages in search of work, believing that they had a 50/50 chance of"making it" in urban areas. 29 But finding employment, especially one that paid enough to support a woman and her family in the countryside, was difficult. A report by the Eighth U.S. Army, which discusses some causes of women's entry into camptown prostitution, states that among women aged 18 to 40 who were living in Seoul in 1965, 60% were unemployed. 30 Although women have served as the backbone of South Korea's economic miracle, through their work in light-manufacturing industries, not all women have had luck finding and keeping viable work."Hyun Ja," a middle-aged divorcée with children, who had no more than a grade-school education, became a GI prostitute as a last resort--factory jobs catered mostly to young women and were therefore difficult to obtain. 31

Still others were physically forced into prostitution by flesh-traffickers or pimps who waited at train and bus stations, greeted young girls arriving from the countryside with promises of employment or room and board, then"initiated" them--through rape--into sex work or sold them to brothels. Women also fell into prostitution by responding to fraudulent advertisements which offered appealing calls for employment as waitresses, storekeepers, singers, and entertainers. Some ads even promised"education" (kyoyuk) without specifying what the women would be expected to learn. 32

For example, one woman who had answered an advertisement for a job in a restaurant found that she was taken to a GI bar. There"[s]he was made to die [sic] her hair blond and wear braless T-shirts and hot pants" and was"beaten into submission" and"forced to provide sexual services" to GIs. This came at the heels of a history of deprivation and abuse; she had been orphaned as a child,"adopted" by a Korean family who used her as a"slave" to take care of the family's four boys, raped by the father, and kicked out by the sons. Then she went to work at a factory and married the owner's son, who physically abused her and abandoned her and their newborn son. 33

The overwhelming majority of the prostitutes have experienced a combination of poverty, low class status, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse even before entering the kijich'on world. Their identities had already become one of"fallen woman." Having lost their virginity and not having much family connections or education to fall back on, these women often expressed that there was not much else they could do; they were already"meat to be slaughtered on the butcher's block" (toma wi e innun kogi). Kim Yonja, who is unusual for having completed high school in the late 1950s, often speaks about being raped at 11 years of age by her cousin as one reason why she entered the kijich'on world. She believes this rape would not have occurred and that her life would have turned out better if her mother had been at home to protect her; but her mother had to work as a traveling peddler because her father had abandoned them.

Since the early 1960s, most camptowns have had a"Women's Autonomous Association" (chach'ihoe) which, in the best of circumstances, functions as a support group for club prostitutes in their interactions with owners

om the perspective of the police and local government, the purpose of the chach'ihoe is to make the women monitor one another in matters pertaining to VD regulations and"business conduct,

Most women support family members with their incomes; earning money to pay for a parent's medical treatment or a brother's school fees is a common motivation in their sex work. A 1965 study conducted by the Eighth Army found that of 105 prostitutes surveyed in the Yongsan area, all"were supporting from one to eight members of their family." 39 Stories about young females working in camptown prostitution to pay for their brothers' high school and university education or their parents' medical expenses still abound in Korea. 40 Ms. Pak, who had sold sex to Koreans before entering a kijich'on club, chose to sell sex to Americans because it would be better for her brothers' futures:

Prior to the Korean War, the sex work of camp followers was informally organized and unregulated. The women who sold sex to U.S. occupation forces from 1945 to 1949, who like other camp followers in other lands at other times, followed or greeted troops with willingness to wash laundry, run errands, and provide sex for some form of remuneration--money, food, cigarettes. Prostitution took place in U.S. military barracks in the early years of U.S. military occupation (1945-46) and in shabby makeshift dwellings called panjatjip (literally, houses made of boards). By the late occupation period (1947-49), simple inns or motels (kani hot'el) also became the loci of sexual exchange

The economic power that U.S. servicemen represented and wielded in the camptowns easily translated into social and sexual clout over Korean kijich'on residents. South Korea in the 1960s became the"GI's heaven"; it was a time when an average GI could live like a king in villages"built, nurtured and perpetuated for the soldiers of the U.S. Army," 56 a time when things American, especially the dollar, were almighty. Men and women danced and drank to their hearts' content with cheap liquor and loud music; over 20,000 registered prostitutes were available to"service" approximately 62,000 U.S. soldiers by the late 1960s. For $2 or less per hour ("short time") or $5 to $10 for an"overnight," 57 a soldier could revel in sexual activities with prostitutes. Servicemen purchased not only sex mates but maids, houseboys, shoeshine boys, errand boys, and other locals with ease. Bruce Cumings characterizes the 1960s as a time when"[o]ne could be born to a down-and-out family in Norfolk . . . and twenty years later live like the country-club set" in Korea, a time when the"highest Korean ultimately meant less than the lowest American in the entourage." 58

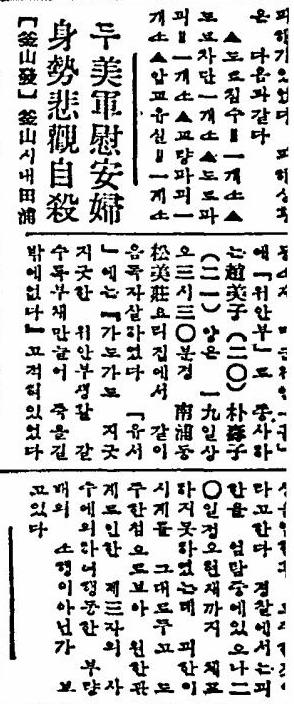

The US soldiers rapes women on the train.(11 Jan/1947 東亜日報)

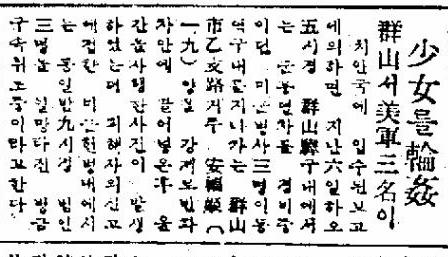

The US soldiers gangraped women 19 years old(11 Nov 1954 東亜日報)

A cofort woman for GIs committed suicide.(21 July 1957 東亜日報)

A african american GI is suspected of murdering comfort women(1 May 東亜日報)

via ☆大韓ニダの介の韓国研究~韓国企業で働いた経験を持つ著者の嫌韓批判&反日批判

4 comments:

She is just another anti-American kyopo. Just like any Kyopo you meet, they hate the USA they hate Japan and they glamorise shitty little korea. Even after leaving they shit shack in Korea they still lie to everyone who has ears that Korea is heaven on earth.

Just like Onishi of NYT?

What she does not also say is that a lot of the college students in Seoul would go to the Bupyong Dong Train station and sell there wares to any GI who walked near them. They always make it look like it was only the poor and destitute who serviced the GI's. Baloney they all did it. I was there and I saw it. There is a lot of truth to what she writes but it was korean's selling Korean's to the GI's. Not the GI's doing the selling which is worse tell me please.

This is nothing but bias writing rather than objective. The writer choose to using negative examples to support her anti-American feelings. GI's did a lot of good for a lot of these girls such as paying their bondage costs etc. One personal experienced example I will share. A houseboy with the 192nd Ordnance Bn one day told some GI's that his family had sold their daughter his sister to a Bar in Paju ri. The GI's collected the $325.00 need to get the girl free went with the house boy to Paju ri to get the girl just in case there was a problem. They all walked into the Arrang Club as his support and we returned with his sister. This is a episode I will never forget.

Post a Comment