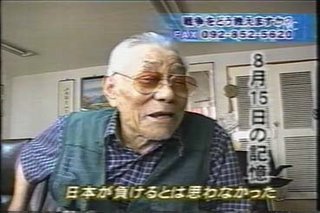

Here is an old Korea gentleman who experienced the cononial period said on TV.

Narator : Li Sang Man (90) was a firefighter. He didn't want to get drafted and passed an exam to be firefighter.

Li : I never imagined that Japan would be defeated. I was so staggered that I couldn't think of what would happen next. Never did I think that Japan would lose. (He is speaking Japanese.)I am the Japanese rightist

Now the blogger is the rightist , so you might think he is biased.Let's look at the book called "under the black umbrella" The author interviewed Korean people who directly experienced the Japanese rule.This is a review of the book.

Hildi Kang developed the idea to write Under the Black Umbrella: Voices from Colonial Korea while listening to her Korean father-in-law tell stories of his experiences during the period of Japanese occupation. Missing from these memories were the accounts of Japanese atrocities preserved in the "passionate stories of martyrs" that she had come to expect. In conducting the research that culminated into her book, Kang came to realize that "under the shade cast by the Japanese presence, some people, some of the time, led close to normal lives" (p. 21).

We can expect that the majority of the people residing on the Korean peninsula during the Japanese occupation would identify with the response that Kang commonly heard when she asked her informants to talk about their experiences: "nothing much happened to me." Indeed, she had to discard a number of her interviews because the informant apparently had nothing extraordinary to relate.

Those who felt their stories worth preserving, though, offered experiences from both extremes: some endured terrible hardships and repression at the hands of the Japanese resident in Korea while others remember this encounter in more positive terms. Watching a Japanese inspector force a farmer to eat the worms that inhabited his grass roof left Chông T'ae'ik with a bitter impression of the colonizers (p. 104). The help and advice that Hong Ûlsu received from his yakuza (Japanese gangster) boss encouraged the businessman through to his graduation from Tokyo's Aoyama University in 1932 (pp. 31-2). It was not always the Japanese who left them their most bitter memories. Yi Hajôn, for example, complained that it was the Korean prison staff members who tortured him (p. 91). Clever Koreans, reported Hong Ûlsu, participated in robbing their fellow countrymen of their land, as well (pp. 12-3).

Many remember their participation (in Japanese institutions) as stimulated by a desire for personal gain; others felt compelled to cooperate. Kim P. (anonymous) reported that she used her father's employment and connections to secure entrance into a better (predominately Japanese expatriate) school. Kang Pyôngju remembered the Japanese "child-catchers" patrolling neighborhoods to "round up children and force them to attend primary school," although education was voluntary at the time (p. 51). His attendance in a Japanese-administered school was decided after his Korean teacher was shot in the leg during the March First Movement. His father, a doctor, had to formally enroll his son in school before he was allowed to administer aid to the injured man (p. 52).Nor were Korean visits to Japanese Shinto shrines always undertaken to demonstrate acceptance of Japanese assimilation policies. Informants remember these visits for reasons other than their respect for Japanese deities. Yi Okpum recalls the visits as necessary for survival: the shrine served as the distribution center for food ration tickets (p. 113). Yi Okhyôn, and other Koreans on Japanese police black lists, took part in Shinto ceremonies to avoid endangering their already fragile existence (p. 114). Ch'u Pongye recalls the beautiful view from the shrine site that overlooked the city of Pusan as ideal for her picnics (p. 114).

Ch'oe P'anbang felt discrimination in his job at the Ministry of Communication: the Japanese got stipends for "hardship assistance" and housing that augmented their already inflated salaries; Koreans were assigned the less popular graveyard shift more frequently than their Japanese counterparts; and the Japanese promoted their kind more readily than the Korean worker (p. 70). Yang Sôngdôk complained that the Japanese received permits to open stores quicker than the Korean merchants did. This advantage placed them in a better position to eliminate any future Korean competition (p. 70). Korean students attending colleges, reports Kang Pyôngju, faced (and insisted on preserving) segregation in all aspects of their lives, from their out-of-school activities to their living arrangements: they did not mix in student committees and resided in dorms segregated by building. Opposition to attempts to mix the two peoples forced plans for integrated rooms to be downgraded to integrated dorms segregated by hall (pp. 53-54)

A number of informants, however, do not recall this time as laden with anti-Korean discrimination. Kim Wôngôk, who worked alongside Japanese on an opium farm, felt that he received equal pay, promotions, and treatment (p. 67) and that he enjoyed a similar experience after being transferred to another job in a different city during the war. His boss, Kim recalls, "looked like a typical Japanese. But he did not talk or act typical," for he criticized his country's "narrow island mentality," likening the Japanese to a "little frog in a little pond." Even more strikingly, Kang Pyôngju was so respected in his village that even the local Japanese police chief would bow to him whenever they passed on the street (p. 59).

The two peoples, united by a shared fate, at times found affinity in their desire to lead a normal life rather than hostility over ethnic differences. One such experience is reported by Kang Sang'uk who recalls exchanging comic books, attending birthday parties, and playing marbles with his Japanese neighbors. He even joined his Japanese friends in poking fun at the Emperor's speeches, although not in public (p. 116). Even people hounded by the Japanese secret police managed to develop a humane relationship with their pursuers. Yu Hyegyông's family fed the detective assigned to watch over her father and eventually they all became good friends. After all, she recalls, "we were all humans" (p. 108).Reviewed by Mark Caprio

On the whole, I think Japanese and Koreans were getting along well in those days.

It is some other people who want to demonize Japanese.

"I last saw sumo here in 1942," said Lee Byoeng-chon, who like many Koreans of his generation was educated in Japanese.

"I've overcome my hard feelings towards Japan. It's often the younger people who are more hostile. They've been fed only the worst stories about the colonial period but they don't know the reality the way we do."

Mrs Kwak Mi-jung in her 40s came with her family. Like many Koreans, she knows little about sumo.

"It's not that I have positive feelings about Japan but I was very curious. This is the first big event since the ban on Japanese culture was lifted. I think we should know more about each other - only then will relations improve."link

Probably both Japanese and Koreans had hard times in those days.But somehow lives went on with or without Japanese rule for most of people.

((see also taiwantaiwan)

崔 基鎬, an old Korean historian, in his book

complains that young historians do not believe what he directly experienced under Japanese rule.He said that Japan's rule was not as harsh as young people imagined, in

fact, it saved Korea.Another Korean professor also points out that Korean collective memory is a fiction and an product of education.[1]

I guess younger generations are interpreting history in a creative ways. that is not bad,But what for?

Update:Korean girls and Japanese girls were getting along

「日本人よ胸を張れ!」“老台北”蔡焜燦氏語る

Note[1}

1910年に日本は大韓帝国を強制的に併合した」

「日本は韓国が植民地だった35年間に、韓国の土地の40%以上を収奪し、膨大な米を略奪していった」

これらが韓国が独立後、40年以上にわたり中学・高校の国史教科書に記載されている内容だ。

しかしソウル大学経済学科の李栄薫(イ・ヨンフン)教授はこうした収奪論が歪曲された神話だと主張した。

収奪という表現は太平洋戦争末期を除き、被害意識から出てきた言葉だと李教授は話している

李教授「日帝(日本帝国主義)が韓国の米を供出、強制徴収したとされているが、実際には両国の米市場が統合されたことにより、経済的『輸出』の結果だった」2004/11/20 朝鮮日報

客観的数値で見ても、奪われた土地は10%に過ぎなかったと説明している。李教授は韓国の歪曲された教科書で学んだせいか、反日感情の根がかなり深くなっていると話した。

李教授「私たちが植民地時代について知っている韓国人の集団的記憶は多くの場合、作られたもので、教育されたものだ」

平成15年11月号(通巻41号)より

寄稿 日本の植民地時代を顧みて

朝鮮は日本の植民地になったお陰で生活水準がみるみる向上した

元韓国・仁荷大学教授 朴贊雄

日本の植民地時代に生まれ、数え年二十歳で終戦を迎えた者として、この世を去る前に、率直な心情を書き残したい気持でこの短文をつづる。

合併当時の事情

合併当時の事情「日本人は平和愛好の弱小民族である韓国を銃剣で踏みにじって植民地化し、36年間、虐政を施しながら土地と農産物を呵責なく収奪した。南北すべての朝鮮人は当時の亡国の辛さを思い浮かべると、今でも身の毛のよだつのを覚える」

これが今の南北朝鮮人の決まり文句になっている。だから、日本は韓国に対して多大な賠償金を支払わなくてはならないというわけで、日本は南の大韓民国に対して戦後賠償金を支払って国交を正常化した。ところが、北朝鮮は北朝鮮なりに戦後賠償を当然のこととして期待しており、日本も、当面の拉致問題が解決され次第、国交正常化して多大な賠償金を支払うことに同意している状態だ。

僕はこのスジガキに対して少なからぬ憤怒感を抱く。

朝鮮が日本の植民地に陥る1905~1910年当時の世界は弱肉強食の時代で、経済力や軍事力のひ弱な国は植民地獲得戦に乗り出している列強が競ってこれを食い物にした。

韓国の当時の経済力や軍事力は列強に比べればゼロに等しいから、当然に日・清・露三国の勢力角逐の場となった。そこを日本は、日清・日露の両戦役を勝ち取った余勢を駆って朝鮮を手に入れた。これに対して、現代人が今の国際規約や国際慣習の尺度で当時を裁くのは不当である。

当時、日本の海軍はロシアのバルチック艦隊を日本海に迎えて全滅させている。日露戦役当時、仁川の沖合いには日本やアメリカ、ロシア等の軍艦が常時出没していたが、韓国には海軍もなければ軍艦もなかったとのことである。

もし韓国が中国やロシアの植民地になったと仮定するとき、韓国の政治や経済の発展は今の中国吉林省内の朝鮮族自治州、あるいは中央アジアのカザフスタンやウズベキスタンに在住する高麗族の水準にしか達し得なかったであろうと思われる。それよりは日本の植民地になった方がよかった、というのが僕の歴史認識である。

今なら世界のいかなる強大国家でも、いかなる弱小国家をも植民地化することは夢想できないばかりか、植民地化したが最後、そこの住民の生活を保障しなければならない羽目に陥ること必然である。故に、ある弱小国家が願ったとしても、まともな民主国家ならおいそれとこれを引き受けるわけにはいかないであろう。

植民地当時の状況

では植民地当時の状況では、植民地化された朝鮮の政治的・経済的・社会的・文化的状況はいかなるものであったのか。

日本の植民地期間は1910年(明治43年)8月29日から1945年(昭和20年)8月15日までの35年間である。保護国になった1905年11月17日からは40年になる。

合併当初から1919年(大正8年)3月1日に起こった全国的な独立万歳デモ事件に至るまでは朝鮮民衆による散発的な抵抗運動が続くが、同デモ事件以後、日本政府は同年8月に朝鮮総督を長谷川好道から齋藤實にかえ、朝鮮統治の原則を武断政治から文化政治に変更してから後は朝鮮民衆による抵抗はとみに衰えた。

軍事力も経済力も組織もない状態で、感情的な抵抗を試みたところで得るところが何もなかろうことは、誰の目にもはっきりと見えていたのだ。

当時の朝鮮は日本の植民地になったお陰で、文明開化が急速に進み、国民の生活水準がみるみるうちに向上した。学校が建ち、道路、橋梁、堤防、鉄道、電信・電話等が建設され、僕が小学校に入るころ(昭和8年)の京城はおちついた穏やかな文明国のカタチを一応整えていた。

日本による植民地化は、朝鮮人の日常の生活になんら束縛や脅威を与えなかった。これは何でもないことのように見えるかもしれないが、独立後の南韓や、北朝鮮における思想統制とそこからくる国民一般の恐怖感とを比べればよく分かる。南北朝鮮人は終戦後の独立によって、娑婆の世界から地獄に落ち込んだも同然であった。

僕のこのような事実描写に対して「非国民」あるいは「売国奴」呼ばわりする同胞も多かろうが、そういう彼らに対し、僕は一つの質間を投げかけたい。

日政時代に日本の官憲に捕えられて拷問され、裁判にかけられて投獄された人数及びその刑期と、独立後に、南韓または北朝鮮でそういう目に遭った人数とその刑期の、どちらが多く長かったであろうか、と。

当時の学校教育

僕の父(1903~69)によれば、当時日本の教師達が学齢期の子供のある家を訪ね回りながら、その父母に小学校に入れるよう頼み込んだそうである。

日本と合併して、日本人の建てた学校に送るのを躊躇した父兄が大分あったらしい。だがそれも束の間、父より七つ下の叔父の時になると、中学校はもとより小学校も入学試験で受験生を選抜した。

寺内総督当時は日本の官吏は文官も含めて、すべて軍服にサーベルを下げていたというが、1919年、齋藤総督に代ってからは文官の佩刀<はいとう>が廃され平服になったという。

僕は1926年(大正15年)10月に京城で生まれ、数え年二十で終戦を迎えた。小学校から中学校の教育をほとんど日本人教師から受けており、終戦当時は京城高等工業の学生として日本人学生と共に学んでいた。だから、植民地時代の朝鮮の有り様については一応総合的な構図を捉えているつもりでいる。

僕の場合、6歳で京城師範学校附属小学校に入学した時、初めて日本人と出会った。一年から四年までは緒方篤三郎先生、五年と六年は朝岡寛一郎先生が受け持たれた。お二方は親切誠実なうえ大らかで、曲ったことは決して受け入れない性格であられた。このお二方は僕の恩人であり、僕の人格形成に影響を与えられた。特に朝岡先生には、僕らが六年になってからは放課後の課外授業もしていただき、そのお陰もあって、僕は名門の京畿中に受かった。

当時、朝鮮内の中学校には朝鮮人だけ、日本人だけ、また、少数ながら韓日共学の学校があった。京畿中は朝鮮人だけの中学校であった。当時、小学校にしろ中学校にしろ、日本人と朝鮮人の学生間には、お互いによそ者という感情はあったものの、敵対感情はほとんどみられなかった。

僕が通った師範附属には日本人専用の第一小学校と朝鮮人専用の第二小学校があって、それぞれ別の運動場を中にして隔たっていた。しかし、僕らは六年間を通して、第一附属の日本人学生と反目やいさかいに及んだ覚えはない。

京畿中の教師は三分の二以上が日本人で、残りの三分の一が日本で教育を受けた朝鮮人教師であった。だから、朝鮮のすべての「教育の淵源」は日本ということになる。僕の祖父、朴勝彬も、合併三年前の中央大学出身で、合併前に大韓帝国の検事を勤めた後に弁護士、それから普成専門の校長を七年間勤めている。

当時の朝鮮人は日本人に対して尊敬はしないものの、軽蔑や敵愾心もほとんどなかった。歴史的事実として、植民地化されている現実を認めて生業を営んでいるカタチであった。だから、親は子供らに対して、学校でよく勉強していい大学を出て、いい職場にありつくことを願うばかりであった。

このような朝鮮人の強烈な、そして通俗的あるいは利己的な親心は今もって変わりがない。独立運動をする親もなければ、子に独立運動をそそのかす親など、ただの一人もいなかった。

著しい人ロの増加

日本植民地時代の35年間に、朝鮮の人口は確実な足取りでほぼ二倍に膨れ上がっている。これは何を意味するのか。

1910年 (明治43年) 13,128,780人

1922 年 (大正11年) 17,208,139人

1934 年 (昭和9年) 20,513,804人

1942 年 (昭和17年) 25,525,409人

1945 年 (昭和20年) 29,000,000人(推定)

これにはいろいろな要因が考えられる。(1)疾病の予防並びに医療制度の向上、(2)豊富とは言わぬまでも食糧の普遍的供給、(3)総督府の誠実な農村振興並びに治山治水政策の奏効、(4)産業化への離陸、というのが僕の推測である。

この中でも、実業家で後に野口財閥を形成する野口遵<したがう>が、咸興に隣接する興南に建てた朝鮮窒素肥料会社の貢献は特筆に値する。

野口は1925年(大正14年)から五年の歳月を費やし、咸興の北にある鴨緑江上流を堰き止め、日本国内にもなかった37万キロワットの巨大発電所をつくる。さらに、それに続いて白頭山や豆満江などに各15万キロワット出力の発電所を建設した。彼はこの電力を利用して空中窒素から硫安をつくるなど、朝鮮の総合的化学工業化に尽くしたのである。

朝鮮に、このような天下泰平の時代がかつてあっただろうか。

終戦後に高まった反日感情

今の若い連中は教科書や小説等の影響を受けて「当時の朝鮮人は皆、日本を敵国と見做し、事あるごとに命をなげ出して独立運動をした。日本の特高が全国的に監視の目をゆるめず、多くの愛国者が次々と捕えられて処刑された」という自己陶酔的な瞑想に耽っているが、これはウソである。

今、植民地時代をウスウスながらも思い浮かべることができる年齢層は、終戦当時15歳に達していた、今は73歳以上の老人達である。それ以下の朝鮮人は他人から聞いて、あるいは学校教育を受けて反日感情に走っている。

韓国人にとって、反日感情はいかにも勇ましく愛国的でカッコがいい。この反日感情が全国を風靡しているので、老人達がそういう国民的合意に逆らう発言をすれば窮屈な思いをする。そのうちに多勢に押されて、逆に加勢するようになる。今や老いも若きも、日本に対する罵声が高ければ高いほど愛国者と遇されているのである。

歴史認識と現実認識

僕が今もっとも憤怒に耐えられないのは、北の金正日政権が日本に対して、歴史認識をなじり、35年間の悪行に対し謝罪して賠償金を支払えと、臆面もなく要求している現実である。

今、北朝鮮国民の苦しみは世界に類がない。飢え死にした者が300万人以上、脱北して逮捕の脅威におののきながら旧満州の地をさ迷う者が30万人にものぼるという。歴史的にもそういう悲惨な例はない。自国民をなぶり殺す現行犯が、日本に対して35年間の悪行を弁償しろなどとよくも言えたものである。

あくどい独裁者の圧政の下に喘ぐ国民の恐怖感というものがどの程度であるかは、体験しない者には分からない。李承晩や朴正煕独裁の下でなんら罪なき国民、特に学生が程度の差はあれ、常に恐怖の中で生きていたことを今の若者達は想像できまい。そのひしひしと迫る恐怖の手綱が1987年の国艮抗争以後、緩んできたのは有難いことであった。

ところが、北朝鮮の金日成・正日父子による独裁の苛酷度は、李承晩や朴正煕の独裁に輪をかけたもので、金正日の代になってもそれは一向に弱まっていない。

近年、南で金大中、盧武鉉の時代になってからは国全体が大きく左に揺れて、金正日に吸収されるのではないかという強い懸念が国民の重大な不安ないし恐怖のタネになっている。これも見逃せない現実である。

日本は、金正日が当面の拉致問題さえ片付けてくれれば、戦後賠償を支払うつもりでいる。だが、そのカネは北朝鮮が民主化する前に渡してはいけない。今、そのカネが金正日に渡れば、それは北朝鮮の軍事力の強化に役立って彼の立場を固めることになり、結果的にその国民は永遠に彼のくびきから抜けきれないであろう。

いや本当のことをいうと、日本は朝鮮を合併してから朝鮮の文明開化にすごく貢献し、朝鮮の文化の基礎を日本流に築きあげた。

それゆえに日本が、これからも西欧の文明を矢継ぎ早に取り入れて日本化していけば、朝鮮は(他のすべてのアジア国家も同様であるが)それを別に苦労もせずにタダで直ちに真似ることができる。これは朝鮮にとってはもっけの幸いである。神様の目からみれば、日本が韓国に賠償するワケはないのである。

逆に、何十人もの日本人を拉致して、彼らとその家族の人生を蹂躙し、これによって全ての日本国民に耐えがたい精神的苦痛を与えた金正日こそ、日本に謝罪し多大な賠償金を支払うべきであろう。link

Koreans have been lied to about the colonial period for sixty years and basically only know the propaganda they have read in their textbooks, which were written to cover up the fact that Koreans were essentially loyal subjects to the Japanese. The United States allowed Koreans to distance themselves from the Japanese after World War II because the US wanted Japan and Korea to be separated.

My mother-in-law talked to me one afternoon about her experiences during the Korean colonial period. She told me that the Japanese were very nice and polite and that she even went to Japan to study. She learned midwifery, flower arrangement, and a secret technique for removing moles without scarring and without them coming back. She said she never saw any of the bad things that Koreans say happened during the colonial period.

I have also talked to a few old men about Korea’s colonial period, but I can only remember the conversation I had with one elderly gentleman about three years ago. I met the old man in a park here in Incheon. He said “hi” to me and waved me over to sit with him on a bench. He started a conversation in English and told me he learned to speak English from working with the US army in Daegu after liberation.

I asked him what it was like during the Japanese colonial period, and he said it was terrible. I then told him that my mother-in-law liked the Japanese and that she didn’t see any of the bad things that Koreans say happened during that time. Then the old man smiled at me and said that he liked the Japanese, too. He then pulled out a Japanese magazine from inside his coat and told me he got it every month and came to the park to read it.

I asked the old man if the Japanese forced Koreans to speak Japanese, and he told me that the only time they spoke Japanese was in the classroom. I asked him what happened when they spoke Korean in the classroom, and he said that the teacher would just tell them to stop. When I asked him why he said the colonial period was terrible, he told me that he just said it out of habit.

I first came to Korea in 1977, and Koreans were afraid to talk about politics back them. If you asked them a question about President Park Chung-hee, they would automatically look around to see if anyone was listening and then would say that they did not want to talk about it for fear they would get in trouble.

Likewise, after liberation, I think Koreans were conditioned not to say anything good about the colonial period, and probably feared being labeled a pro-Japanese traitor if they did. Today, Koreans are still calling people traitors for being pro-Japanese, but, at least, there is not the fear of being arrested. Today, if elderly Koreans are still saying that the Japanese colonial period was terrible, they may be just saying it out of habit, like the old man I met in the park. Next time, you talk with an elderly Korean, try asking him or her for some details of his or her life during that period. They may end up inadvertently telling you that life was not so bad.Gerry

No comments:

Post a Comment